Alimentation Couche Tard: A Cheap "Future Proof" Industry Consolidator

Something Amazon can't disrupt? A hot dog and soda pop.

When I buy a company, I like endurance. I like grit. I like a business ready and adaptable to change or a business that doesn’t have to change.

One such business example is the local convenience store you can find near your home.

Whether you live in a city or in a rural area, a convenience store represents several things. Easy access to fresh groceries, food, packaged food, drinks, a coca cola, a root beer, or just a candy bar and some popcorn, or even cup noodles (especially Asia).

Know what disrupts those?

Nothing. Absolutely, nothing.

Amazon will never want to be in the business of delivering a hot dog, a candy bar, three packs of beer, and six cans of coke to your house unless you give them a monthly subscription - and even then it’s suspect.

Can they do it cheaper and better versus an already established convenience store? Maybe. Would they want to? Probably not.

Not unless the purchases are regular and increase the routine relevance of their delivery system.

In this sense, convenience stores serve as the “last mile delivery” for immediate need products - the above consumables.

And I like it when a business can’t get “Amazoned”.

Some numbers:

FY20 Free Cash Flow: $3,090 million

Enterprise Value: $$53b

EV/FCF approx: 17x

Ticker: $ATD.A/$ATD.B

It’s been awhile since I’ve actually found something I like. Awhile ago, I spun out a simple returns on invested capital screener on and decided to see what pops up. Along w some other unusual names - this one stood out.

The name caught my eye by pure luck - what kind of management names themselves after what sounds like a gastrointestinal disease?

As it turns out, Alain Bouchard does.

The rest of the names are still names I’m taking a gander at, but ATD is one of those companies I’m relatively certain I have to do little in order to buy into.

For those unfamiliar with the business operations;

There are several key reasons I like shares of ATD. But first, let’s run through a simple quantitative exercise and check if our rationality is still present.

What would you pay for company with the following characteristics?

12-15% average return on invested capital over the past decade

grown revenues 3x since 2011

grown Gross profit 4x ~~

grown operating income 6x ~~

grown net income 7x ~~

grown free cash flow per share from $0.35 to $2.40 (21.23% cagr)

with minimal debt (debt to equity: 0.52), or 6.3bn debt vs 12.1bn equity, 2.7bn in cash and cash equivalents.

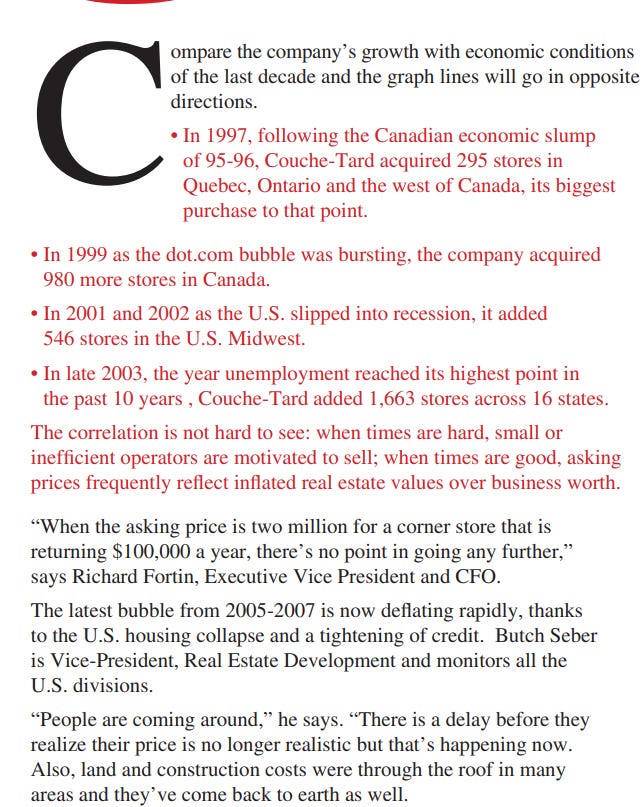

low cyclicality and exposure to economic recessions, with sales going through 5-8% growth during both the dot com bubble burst as well as the 2007-8 financial crisis.

2020 numbers:

revenue: 43bn

fcf per share: $2.40

If you baked the above facts and data into mind, you should be able to distinguish (a) that the convenience store chain business, pretty much the oldest -most boring business there is - has not yet been disrupted, (b) the company is offering above bond like returns at 5% free cash flow yields, (c) without baking in organic growth or growth via acquisition, (d) without baking in share buybacks (of which there has been plenty at opportune times) and dividends (0.89%) currently.

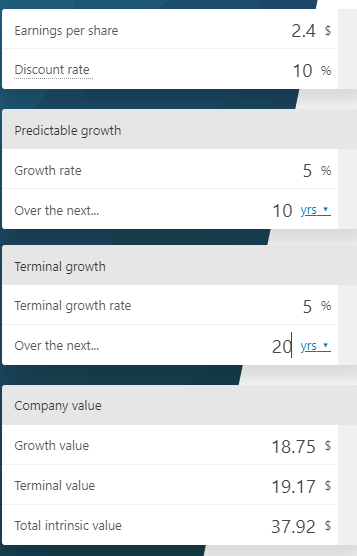

You don’t need to be a genius based on the numbers above to see that we do have quite a large margin of safety based on current valuations. Bear in mind the $2.40 above is based on free cash flow per share data. Historically, the CAGR of FCF for ATD has been 27.34%. Let’s take this with a pinch of salt and slice it down to 10% versus the illustrated 5%. What happens?

Total intrinsic value jumps to about $50 per share even with an 11% discount rate.

From a quantitative standpoint, it’s a screaming buy.

But what drives growth?

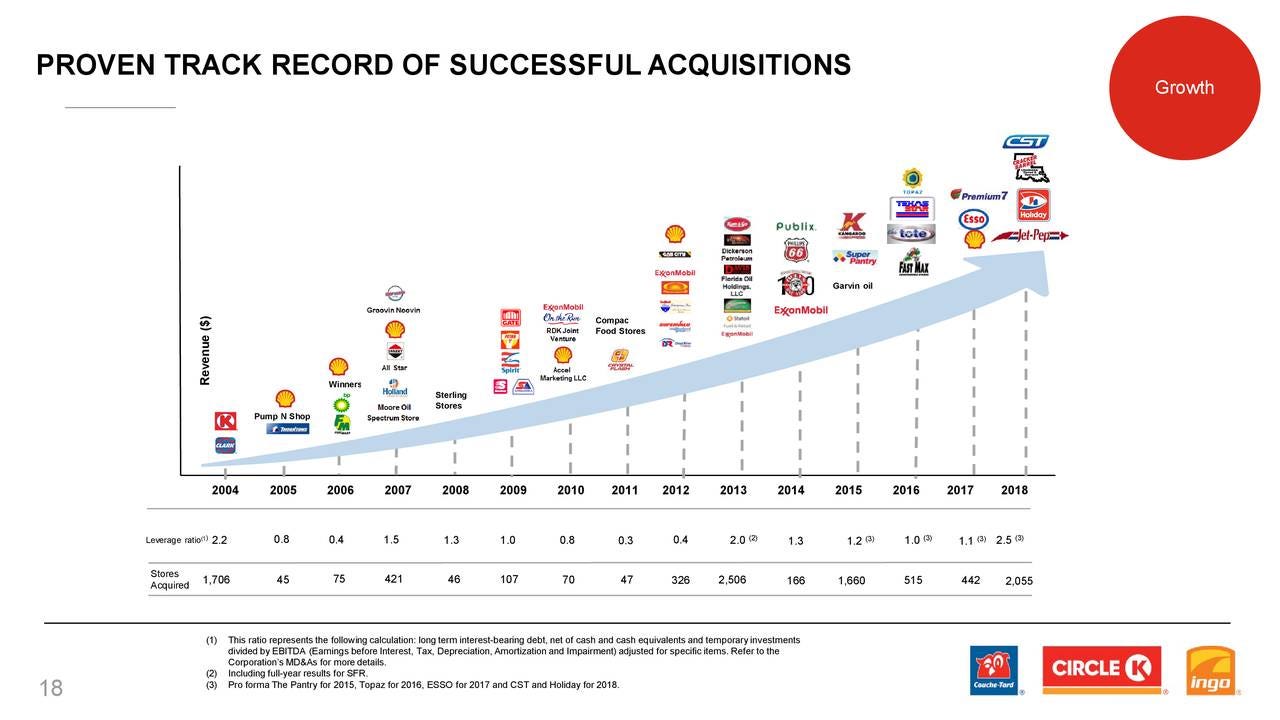

In the case of Alimentation Couche Tard and the C-Store industry in general, organic growth and acquisitions are by far the most efficient ways to “grow” the business.

To understand why, let’s take a look at the C-Store industry and various other metrics and statistics I’ve pieced together.

Existence of a Moat: Snowballing Profitability, Scale, Cost Control, Pricing Information Advantage, Decentralized Management

All moats - no matter how conceptual and abstract they are - must have some form of evidence within the numbers.

Couche Tard bears this out with stunning evidence. Return on Capital has hovered between 12-17% on average versus industry peers averaging 6-8% for similarly sized peers. Return on Equity has consistently been above 15% and averages 20% over the past 10 years.

Free cash flow as a percentage of revenue (cash generation ability) has risen slowly, going from 2.09% in 2011 to 4.27% in 2020. It is clear from any quantitative point of view that Couche Tard is doing something right.

How is Couche Tard sustaining their “moat”? Why have competitors not yet diluted excess returns? The decade long numbers above indicate to me that this isn’t some mere chance. 10 years of industry outperformance for returns on capital cannot have been the byproduct of luck.

As I’ve noted in earlier posts, scale matters in a low margin business. Greater purchasing power begets bigger discounts which lets you price out competitors or decrease the cost of goods in a low competition environment. Couche Tard’s net margins reflect this economic reality, averaging between 3-4%. Most comparable peers average 2%. A 1+% difference is a gaping abyss when you consider billions of dollars retained over years.

Why?

Because retained earnings and free cash flow snowballs and the bigger you get, the harder you get to swing. Acquisition opportunities, purchasing power, leverage over suppliers and vendors all come into play when you get bigger, faster than everyone else.

A fun allegory.

The player with greater “worker count” with which to mine resources in Starcraft 2 soon takes the economic lead and thereafter the “upgrades” and “army size” lead, which in turn snowballs even harder into areas of control and access to expansions which in turn lead to even better upgrades and even bigger army sizes until one side has a larger, more upgraded, more sustainable army production and force projection and then just overwhelms the other guy.

This is the same in business. And that incremental edge grows over time and soon becomes an edge too great to surpass. That Alimentation Couche Tard has managed to grow revenues, operating cash flows, free cash flows, and net income at a level unprecedented.

I can’t find a single convenience store retailer sporting similar returns on capital or even just slightly under that has grown at such a scale. There is something to be said about a well capitalized, well-run, efficient convenience store retailer gobbling up chain stores, finding synergies, eliminating bloated costs, deleveraging, then rinsing and repeating over and over again.

Cost control has been judicious despite large acquisitions.

For a comparison, 7 and I Holdings has barely grown revenues over the past decade, going from roughly 45b-65bn in revenues whilst Couche-Tard has grown from 17bn to about 76bn.

In my view, I believe that the consolidation strengths of Couche Tard is understated. All large players within the C-store industry utilize acquisition as a form of growth. But most of them fail to achieve overall efficiency post integration at the asset level.

I looked through the ROA as a measure of efficiency for several retailers in roughly similar spots and most sport half the return on assets that Couche Tard has. This cost cost control culture is not simply a one time occurrence. It is rooted in the DNA of the company. Alain Bouchard, the founder, knew that the only way to justifiably eke out a large edge over time is to focus on the pennies.

Evidence, appendix 1:

Appendix 2:

Appendix 3:

Appendix 4:

For comparison’s sake, I have yet to find a single large, well-established competitor have such an large and continuous focus and control over costing that they’re focused even on the pennies. A rather famous allegory here can be found too in Pepsi vs Coca-Cola as elaborated by Warren Buffett.

The difference a penny makes, as it turns out here, came up to about $6 billion. I don’t know about you, nor do I know about others, but I think there’s a big recurring pattern here about frugality and focusing on costs and expenses over time.

Couche-Tard’s DNA has been cost control, integrations, realizing synergies, deleveraging, and onboarding more and more chain stores to rapidly increase cash flows over time.

And they’ve done it well.

Like the Tarmogoyf, a beast that grows ever large with each kill, Couche-Tard gains ever greater synergies and cashflows. It becomes better able to utilise existing delivery routes, and optimize merchandising. It comes better able to reflect fuel prices, food prices, drink prices across entire countries. It’s benchmarking continues getting better. It’s cash generation ability improves, and the acquisition opportunities grow.

This is a flywheel like almost any other - Roper, Constellation Software, Topicus.

A good dig through older annual reports also show why the management team has been able to produce such exceptional results.

And perhaps the most important edge: the business gets better when bad times come along through both opportunistic share repurchases and ideally, more acquisitions.

A small side note: decentralized management structures make it possible to run large organizations effectively by permeating the culture of the company through down to the man/woman on the floor.

As Mark Leonard, CEO of Constellation Software, a serial VMS acquirer and true compounder focused operator put well;

While we have developed some techniques and best practices for fostering organic growth, I think our most powerful tool is using human-scale BU’s. When a VMS business is small, its manager usually has five or six functional managers to work with: Marketing & Sales, Research & Development ("R&D"), Professional Services, Maintenance & Support and General & Administration.

Each of those functional managers starts off heading a single working group. If the business leader is smart, energetic and has integrity, these tend to be halcyon days. All the employees know each other, and if a team member isn't trusted and pulling his weight, he tends to get weeded-out. If employees are talented, they can be quirky, as long as they are working for the greater good of the business. Priorities are clear, systems haven't had time to metastasise, rules are few, trust and communication are high, and the focus tends to be on how to increase the size of the pie, not how it gets divided.

That's how I remember my favourite venture investments when I was a venture capitalist, and it's how I remember many of the early CSI acquisitions. That structure usually suffices until there are perhaps 30 to 40 people in the business. At that stage, some of the teams - perhaps R&D if the product is rapidly evolving or has high needs for interfaces or compliance changes - must grow beyond the five to nine optimal team size. If the head of R&D in this example is brilliant and is willing to work hours that are unsustainable for most of us, he may be able to parse out tasks for each of the team members despite the increased team size. He may be able to judge the capabilities and cater to the development needs of each of his direct reports. He may be able to recruit excellent new employees, and he may be able to manage the demands and trade-offs required to co-ordinate with the other functional managers.

The more likely outcome, is that the R&D manager isn't a brilliant workaholic and cannot cope as the team size exceeds double digits. Instead, he'll break his team up into multiple teams. A new level of middle managers will be born, with all the potential for overhead creation, politics, and bureaucracy that comes with another tier of middle managers. The larger a business gets, the more difficult it becomes to manage and the more policies, procedures, systems, rules and regulations are generated to handle the growing complexity. Talented people get frustrated, innovation suffers, and the focus shifts from customers and markets to internal communication, cost control, and rule enforcement. The quirky but talented rarely survive in this environment. A huge body of academic research confirms that complexity and co-ordination effort increase at a much faster rate than headcount in a growing organisation. If the BU is small enough, and has a competent BU manager who has several years experience in the vertical, and good functional managers, then he/she will be able to cope with complexity for a while, making the right calls to optimise organic growth as the business grows. The challenge of running a BU of this size is human-scaled. As a BU becomes larger (by our standards, that’s greater than 100 employees), I worry that even an extraordinarily brilliant and energetic manager, who has been in the vertical and the BU for a very long time, and is surrounded by a strong team that he/she has selected and trained and winnowed over many years, is going to struggle to steer the business to above industry average organic growth.

No one wants to admit that they’ve hit their limit. Some BU Managers lack the humility, some lack the courage, and most lack the time for reflection, to notice that their task is getting too large, and the sacrifices are getting too great. This is the point at which our Operating Group Managers or Portfolio Managers can provide coaching.

If a large BU is not generating the organic growth that we think it should, the BU manager needs to be asked why employees and customers wouldn't be better served by splitting the BU into smaller units.

Our favourite outcome in this sort of situation is that the original BU Manager runs a large piece of the original BU and spins off a new BU run by one of his/her proteges. Ideally, he/she has been grooming a promising functional manager who’ll be enthusiastic about running and growing a tightly focused, customer-centric BU.

This dividing of larger BU’s into smaller units is rare, but not unknown, in other large companies. One of the HPC’s that we studied was Illinois Tool Works Inc. (“ITW”). It has hundreds of BU’s. We began following the company from afar in 2005. The most relevant period in ITW’s history for CSI was the tenure of John Nichols. Nichols began consulting to ITW in 1979, and appears to have been the primary author of its decentralisation strategy. He was CEO as the company went from $369 million in revenues in 1981 to $4.2 billion in 1995 ($6.7 billion in today’s dollars). Prior to Nichols's tenure, ITW had acquired only 3 businesses.

During his tenure, ITW aggressively acquired and often split the larger acquisitions into smaller BU’s. ITW had 365 separate operating units by 1996 when Nichols retired.

I’m sorry I didn’t reach out to some of the ITW employees and ex-employees until 2015.

When I did talk with one of the senior managers, he said (I’m paraphrasing) “Something wonderful happens when you spin off a new business unit.” … “With a clean sheet of paper, the leader only takes those he needs. They set up in an open office with good communication and no overheads. They cover for each other. They leave all the bureaucracy and the crap behind”. I did record a couple of verbatim quotes from that conversation: "Don't share sales, R&D, HR, etc. because the accountants never get the allocations right and the business units always treat the allocated costs as outside their control", and "When you get big, you lose entrepreneurship".

Mark Leonard, CEO, Constellation Software

The simple fact is, no one man can control hundreds of thousands of employees. Store managers must be held responsible for the job and rewarded accordingly.

In this regard, Couche Tard has done well. This is but one example.

Summary: I believe cost control, great synergistic realizations, a relentless focus on even the pennies in the system, the decentralized management structure, the resulting slight increase in free cash flow versus other firms, and Couche Tard’s discipline acquisition culture has allowed it to amass significant M&A plus pricing competitive advantages. These are advantages that will only get larger as the firm reinvests more money into the business.

Capital Allocation & Industry Specifics

Most industry specific circumstances can be gleaned by virtue of common sense - low margin business rely on volume, purchasing power, the ability to reduce costs and drive out competitors with less purchasing power, and then subsume them over time. This isn’t hard to figure out.

Even if it were hard to figure out, reading the annual reports over the past ten years for any company in any industry, along with the annual reports of its largest competitors as well as their presentations can more or less confirm theories you should draw up prior to reading. I say this because you must be able to disclaim a thesis. And you must also be able to withstand the immense marketing power of the Investor Relations departments embedded with each company. If you want to know where the best copywriters in the world are, they’re at every investor presentation pitch making department ever. It’s their job to sell you a sexy story. Most of the time, the numbers fail to illustrate this “happy” economic reality.

I’m glad Couche Tard did disprove it for me. My understanding of the industry was granular - I have spent time as a boy stocking shelves and as a student repacking pantries. Costing, purchasing power, is everything. The larger you are the better off you are. Conversely, the smaller you are, the more likely you will fail. Smaller companies cannot manage manpower costs, purchasing power, margin pressures, fuel price (buying spot high but selling at the pump prices 3 days ago is a great way to lost boatloads of money) pressures, and competition all at the same time. Consequently, a large number of them fail.

This tobacco contraband issue is but one example.

Credit card fees are yet another.

In understanding where growth comes from, sometimes, it’s just easier to see if there are other serial market share donators for the company you’re looking at.

In this case, the industry represents fantastic news.

Statista puts 2019 total sales of C-stores at about 650 billion. If this number is accurate within a degree of confidence, then Couche Tard represents slightly under 6% of total sales.

Put in a slight bit of growth from 2019 - 2021 and you can say 5% is about correct. So the company isn’t bullshitting you. They’re presenting facts as they are. If this is true, the largest, most opportunistic, most capable synergy extractor should be able to bang out between 5-10% growth in revenues/free cash flows.

Let’s take this with a grain of salt. Let’s call organic growth about 3-5% per year. Combine that with 5-10% and you get between 8-15% growth in intrinsic share value every year on top of a 5% fcf yield. Assuming no share price multiple compression (at 14x earnings, I can hardly see the reason to be honest), Couche-tard should be able to deliver double digit forward rates of return. Add in a yield of .89% that goes up over time and I think I’m firmly in the “safe” zone.

This is without considering the remaining factors;

(a) Alain Bouchard reaches 65 by December 2021. This triggers a share ownership structure change which means that the original four founders would not be able to effectively control the company completely. Since ownership is not “passed on” so to speak, private equity and other companies might make a big, triggering a value unlock. Note that Casey’s currently trades at 27x earnings sporting inferior growth rates.

(b) the fresh food initiatives observed across most c-store industries that are driving higher margins and greater sales is an initiative we have yet to see play out fully. This is certainly one concept I’m excited to see Couche Tard implement and handle over time.

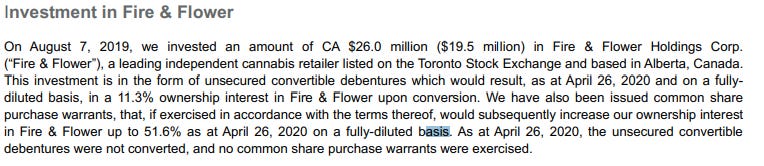

(c) the company currently holds shares in Fire and Flower, convertible to a full 51.6% ownership if Couche Tard remained interested. The cannabis market is side by side with the tobacco market. I remain intensely aware that any retailer capable of selling weed legally will likely enjoy much higher margins and sales growth over time, particularly after it’s been made legal.

(d) company executive team buy in is required. this ensures skin in the game. I’m happy and relieved to see this. I do wish they’d included it in the main 10k however. Eurgh.

Talking about skin in the game, note that the original founders hold nearly 85% of all Class A shares. I’m not too worried since the executive team hasn’t fucked shareholders over, but by jolly is that a lot of “skin in the game”.

(2b) management has also consistently NOT fucked shareholders over via costs, mostly costing shareholders sub 1% of EBITDA. I’ve seen some truly horrific compensation plans that take the cake, and this is true owner oriented thinking in action.

(3) above, i penciled out about roughly 8-15% returns over time. this did not include share repurchases, optionality on the cannabis markets, larger and accelerated industry consolidation, and more importantly, large and consistent share repurchases in the event of material share undervaluation over any sustained period of time.

Note the evidence for 08 and recently, 19.

2009,

2019, when shares traded around 15-17x earnings.

The company has bought back more shares in 2011, 2012, and 2018 as well. I do not expect this pattern of behavior to discontinue anytime soon. Anytime shares represent significant value, I believe the management team will take advantage and swing hard.

Summary

In sum, I believe a tight and rigorous cost control mindset put out at the start allowed Couche Tard to gain a tiny free cash flow edge which incrementally grew via acquisitions, cost control initiatives, synergy realizations (eliminating unnecessary back office operations, sharing one accountancy office, heavier utilization of fleet, increased purchasing power), a decentralized management structure, an emphasis on returns on capital and disciplined acquisition, opportunistic share repurchases, a fragmented and opportunity ripe market, and greater downside opportunities (more acquisitions and share repurchases!), economic resiliency, all add to the attractiveness of Couche Tard Class B shares at $35 a share.

Notes

*greater exposure to rapidly increasing fuel prices from fuel pump dynamics

*covid19 did slump sales. not the same as an economic recession.

*catalyst event: Dec 2021, share ownership structural change

Disclaimer: I own shares of Alimentation Couche Tard. Do your own due dilligence. Good luck.